ART/CULTURE

Your Idea is Bigger Than Your Media

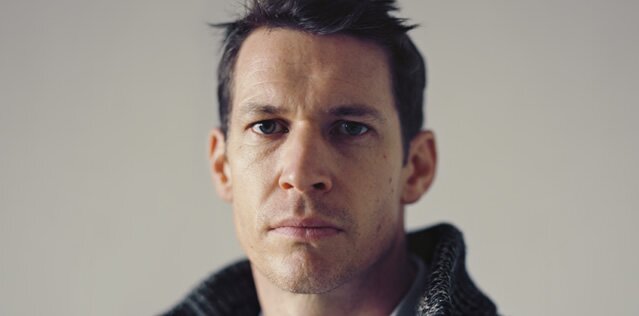

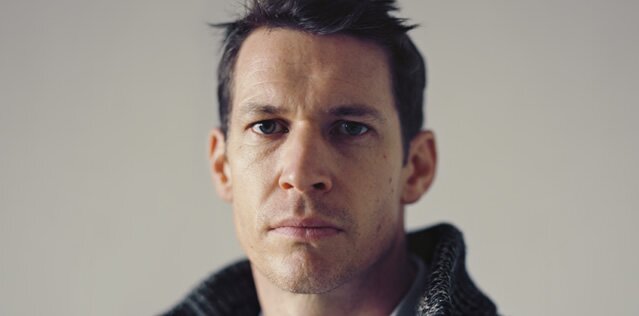

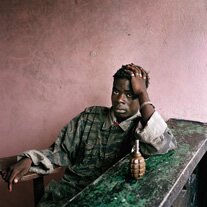

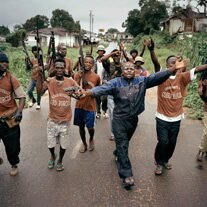

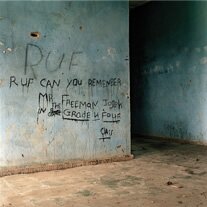

It has been a full year since Tim Hetherington was killed while covering the front lines in the city of Misrata, Libya during the civil war. But today he continues to inspire many of us through the work he left behind and the stories his friends and colleagues keep telling. His solo show is on view at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York through May 19th.

When we started to prepare for the 0 issue of PERISCOPE, Tim Hetherington was one of the first people we went to. That was because we thought his approach to his work in conflict zones was so much more than what we think of "photo journalism." I had met him in 2008 through a mutual friend and subsequently asked him for an interview. He had just come back from Afghanistan where he and Sebastian Junger shot a feature-length documentary Restrepo. After his life was taken away, we revisited the recording of the interview.

RSS Feed