ART/CULTURE

Luke Murphy Interview

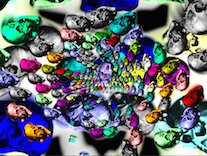

Luke Murphy is a New York-based artist who grew up in Canada through the end of the Cold War era. Upon seeing Luke Murphy’s work, you’d never guess what compels the piece into creation. Radiation, anxiety and randomness are three key concepts that form his computer generated art. In his youth, he became obsessed with Geiger counters and country music. Eventually, he figured out how to make art based on radiation counts. With the Cold War over, we still deal with radiation scares in different ways such as the situation in Fukushima and fracking in Pennsylvania, a process which some experts say brings radiation to the surface that had been trapped in the ground. This is why Luke’s attempt to turn intangible things like radiation and randomness into a form raises interesting questions about the world we have come to live in.

RSS Feed