ART/CULTURE

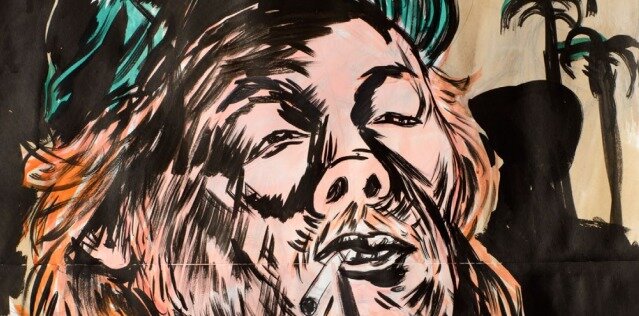

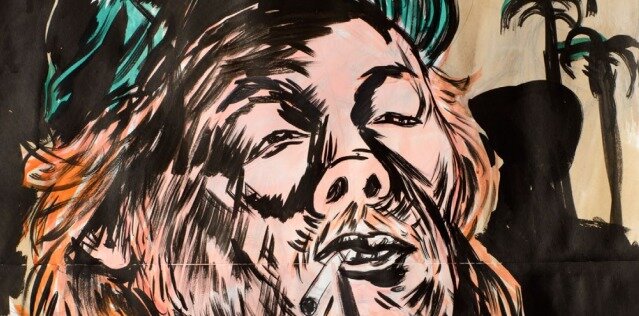

Mark Taylor Interview

Mike Taylor is a Southern bred, Brooklyn-based artist who organically incorporates screen printing, painting, drawing and text into his work. He is informed by different influences from subcultures, namely comics, zines, and Punk. With his first solo show in New York in March 2014 titled “NO/FUTURE,” he addressed the political and cultural mythology of the United States.

RSS Feed