MUSIC

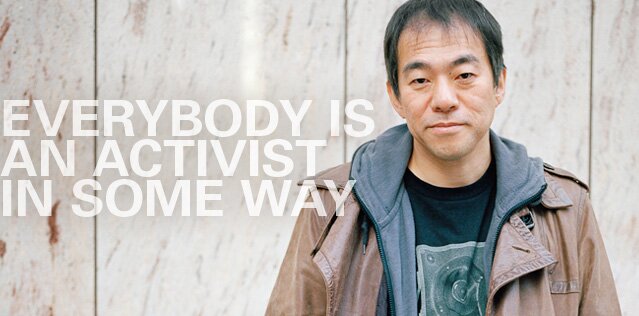

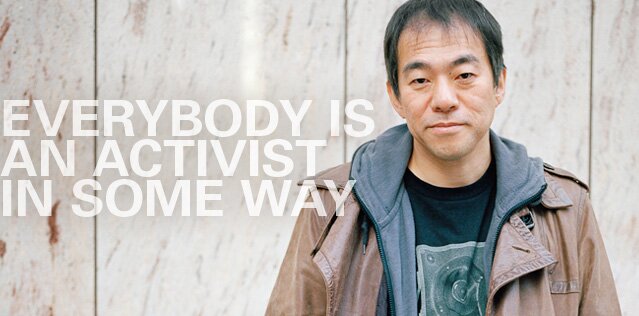

A Reluctant Activist

Otomo Yoshihide, an experimental music giant from Japan who is probably most well known as the leader of the 1990s noise rock band Ground Zero, has recently become a de facto activist representing the people of Fukushima in the wake of the nuclear power plant crisis. He started a UStream TV station, Dommune Fukushima!, and on August 15th, he hosted a music and arts festival FUKUSHIMA!.

Late last year, he came to New York to play a show with Christian Marclay and Periscope caught up with him.

RSS Feed